Classifications

Objects in QuPath can each have one classification.

Sometimes the classification is null, indicating that the object is ‘unclassified’.

At other times the classification might have been set manually by the user, or automatically using machine learning.

Both processes of setting classifications have already been described; here, our focus is on how the classification really works.

Classifications & derived classifications

The fact that an object has only one classification initially seems very limiting.

However, a lot of information can be encoded within the classification. This is because classifications in QuPath can optionally be derived from other classifications.

A common example of this is when cells are subclassified according to staining intensity. The Cell classification tutorial shows the example of cells being classified firstly as Tumor or Stroma. These are the base classifications. The cells were then subclassified as Positive or Negative.

This two-step process produced four distinct classifications:

Tumor: Positive

Tumor: Negative

Stroma: Positive

Stroma: Negative

Each cell then had one of these four classifications.

There is nothing special about the base classifications Tumor and Stroma; these could be swapped for anything. But the key thing is that all four classifications are distinct and can be applied to any object, yet all four encode information that enables QuPath to determine their similarities.

Consequently, QuPath is able to automatically give not only the numbers of cells with each classification, but also the numbers of tumor cells and stromal cells separately, and the percentages of positive tumor and stromal cells (both separately and combined).

Hierarchies of objects & hierarchies of classifications

One can think of classifications and subclassifications like a hierarchy, with ‘base’ classifications and then other classifications derived from them.

Visual example of the hierarchies of classifications and subclassifications

This is reminiscent of the object hierarchy, but in practice they are quite distinct.

One important difference is that each classification knows the classification from which it has been derived (if any). But it does not know any classifications that have been derived from it.

In other words, one can take the classification Tumor: Positive and immediately see that it has a parent classification Tumor. But if we have the classification Tumor, we don’t immediately know what - if any - subclassifications exist. This is unlike the object hierarchy, where you can start with any object and then query both its parent and its children.

This makes sense: the actual classification applied in QuPath is the one that contains all the required information. One can then ‘look upwards’ to determine all the pieces of information that have been encoded within that classification by checking the names of the classifications from which it has been derived.

Intensity classifications

From the classifications mentioned above, there is nothing special about Tumor and Stroma.

There is however something special about Positive and Negative. These are examples of intensity classifications, and they are used by QuPath to automatically create summary statistics such as the percentage or density of positive cells.

Other intensity classifications are 1+, 2+, 3+, which are used to indicate weakly, moderately and strongly positive staining - used to dynamically calculate H-scores.

H-scores

H-scores are commonly used in pathology, as they are (somewhat) amenable to visual evaluation in a (kind of) quantitative(ish) way.

H-scores are calculated by estimating (or otherwise determining) the percentage of cells in each category (Negative, 1+, 2+, 3+) and multiplying this by the number associated with the category (0, 1, 2, or 3) - then summing the results.

The results then range from 0–300, where 0 indicates ‘all cells are negative’, and 300 indicates ‘all cells are strongly positive’. There are different routes to H-scores that fall between these limits.

Double-positive, triple-positive

The standard intensity classifications above are fine if there is one thing that each object might be positive for.

It isn’t enough if there are multiple things, e.g. counting double-positive or triple-positive cells. In such cases, we need to find a more creative way of applying QuPath’s classifications.

The Multiplexed analysis tutorial shows this in action. Here, we create derived classifications where each component of the classification indicates that the cell is considered positive for the marker with that name.

We no longer need Positive and Negative subclassifications; rather, if a cell is (for example) CD3 +ve then its classification contains one component with the name CD3. If its classification does not, the cell is considered to be CD3 -ve.

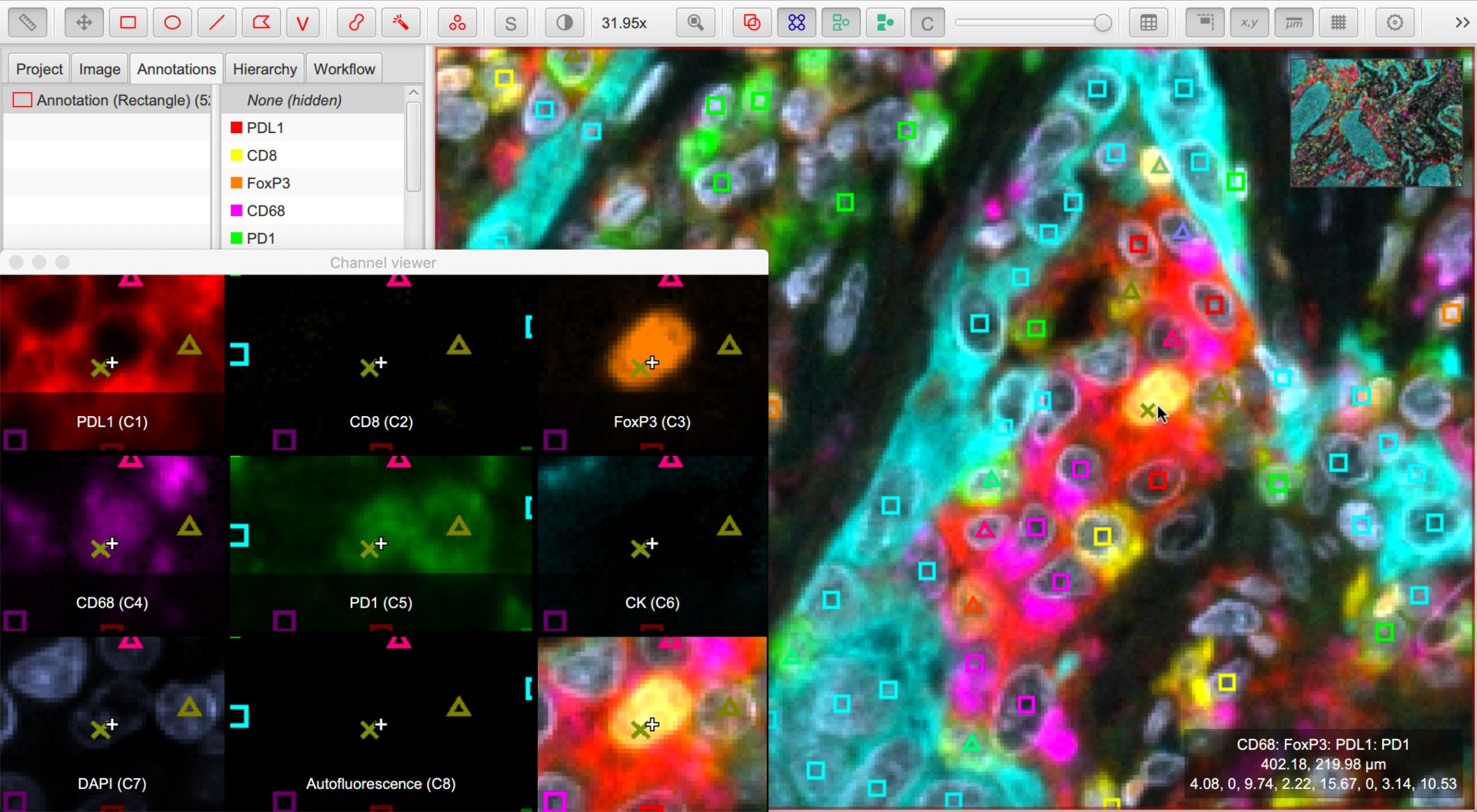

Multiplex analysis showing centroids of cells that are positive for various classifiers

Ignored* classifications

There is one other classification concept, which is a relatively recent addition to QuPath: that of ‘ignored’ classes.

These are like normal classifications, but under some particular circumstances they are… well, ignored. This includes when making measurements or converting classifications to objects.

You can distinguish these classes by the asterisk at the end of their name, e.g. Ignore* and Region*.

Why have ignored classes?

Ignored classes fill the gap between objects with meaningful classifications and those that are completely unclassified. One reason this is necessary is because unclassified annotations cannot be used to train a classifier – but we often still need to identify regions we aren’t interested in so that we can distinguish them from the regions we are interested in.

They are basically a way to express ‘I want you to find this, so that you can ignore it’.

Ignored classes are also useful with thresholding for situations where you wish to identify regions but don’t necessarily care what classification they might have.

Tip

I typically use Ignore* for areas of whitespace or artifact.

I use the Region* class to define areas where I don’t care what the classification is – but I do still want to distinguish it from anything that is unclassified.